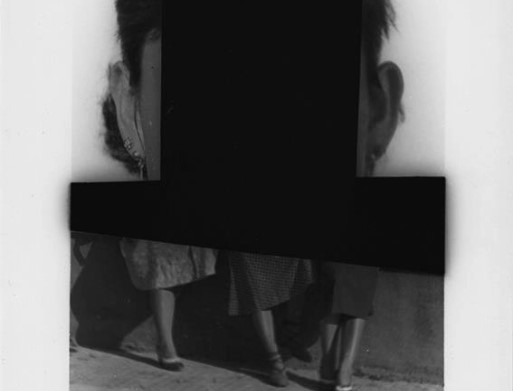

The Spectre of the People

If once the spectre of communism haunted Europe, now the spectre of populism stalks the Earth. Artists have grappled with its myriad dimensions: how and if to represent ‘the people’, how to represent democratic power, the nature of charismatic leaders, and popular protest and insurgency. The media of the lens, long woven tightly around the history of mass politics, have been a natural field for this artistic exploration.

The main exhibition of the 2023 Thessaloniki Photobiennale, The Spectre of the People, explores populism through photography and video: who are ‘the people’, can they be grasped visually, are they the source of hope or dread, how are they condensed in the figures of their would-be leaders, and how do they assemble and act in political protest?

The artists shown here approach these issues in widely contrasting, if sometimes overlapping, ways: some document populist leaders and their followers, and by contrast those people declared enemies by populist movements; some offer satirical takes on the absurdities of authoritarian leaders and the political delirium that they create; others perform as populists or make activist work in solidarity with protest movements; others again offer conceptual works on populism, and the deep economic crisis from which it drew strength.

The exhibition is divided into four main parts. The first two are shown at the MOMus-Thessaloniki Museum of Photography: part one explores artistic responses to the fraught dilemma of how to represent mainstream democratic politics, especially as it falls into crisis. Part two looks at populist leaders and followers, along with the deadly consequences of their actions. The next two parts are shown at the MOMus-Experimental Center for the Arts: part three envisions those who are excluded from ‘the people’ by populist movements, set alongside the very rich who do all they can to insulate themselves from the rest of us, and the means used to police the boundaries. Part four tracks the performative culture of insurgent protest movements of both the left and the right.

Like the phenomenon of populism, the exhibition has a global ambit. This scope makes the elusive concepts of ‘the people’ and of populism harder to tie down, as they span continents, the left-right divide, and often tie together mass participation and authoritarian rule. Yet from the very diverse works on display, there emerges an image of the populist field as it oscillates between the poles of political antagonism and solidarity.