Photography since its advent has emphatically showcased the portrait as a reflection of individual and social identity, as a dialogue (fragmented but increasingly dense) with personal and collective memory. In the first decades of the new medium, photographs were realized in studios with the skills and conventions of emerging professionals, in a more or less artful way that spread across countries and continents in a more or less colonial context. As the medium became more and more popular and easy to use, people started to create their own casual snapshots of close friends and family.

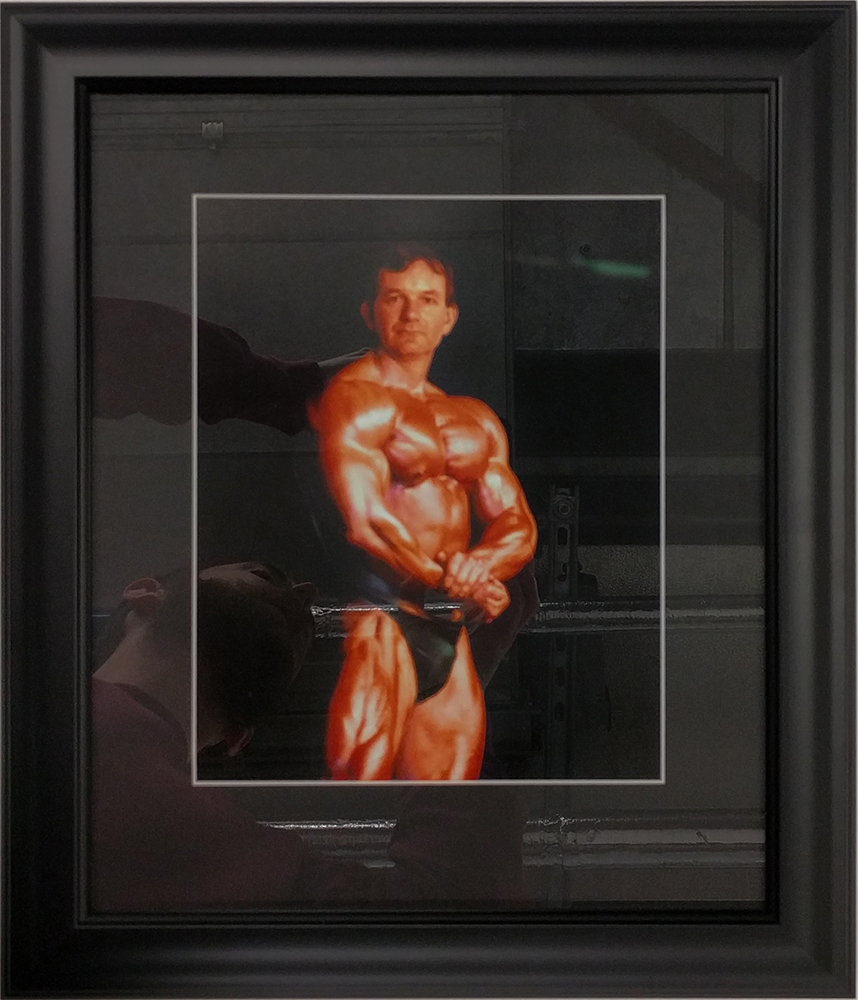

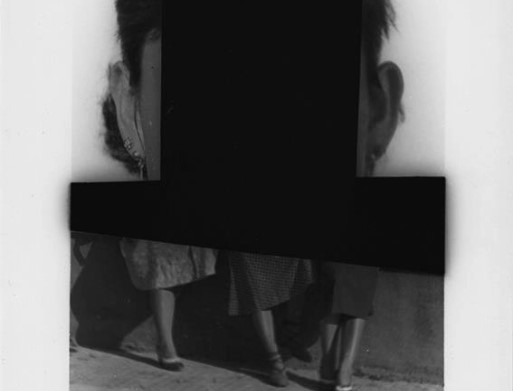

In the twilight of the 20th and the dawn of the 21st century Martin Parr, while travelling on international media assignments, began to get himself pictured in studios and photobooths all around the world. His figure gradually became part -physically or digitally- of diverse settings, designed to validate stereotypes or generate new ones. In these photographs, contrary to the banality of traditional studio portraits, a local attraction or landmark, an imaginary character or the cardboard effigy of a leader attempt, in versions occasionally flirting with kitsch, to offer the depicted person a notable, prefabricated memory. For twenty years (1996-2015), Parr would surrender himself in a willing, expressionless manner to the hands of his peers, consciously becoming prey to a mechanism of standardized images. This witty series, which inadvertently heralded the current narcissistic flood of selfies, bears stark testimony to the way photography became catalyst of an early globalization process, magnifying the local and discovering the exotic, thanks to its unique ability to travel, assimilate, adapt, reproduce itself, generate a certain aura.

The self is here surrounded, from one image to the next, with a blithe fluidity, as it poses in all sorts of atmospheric settings, bygone or futuristic, flamboyant or austere, culturally specific or all weather. These portraits ultimately gain their vitality from the gradual realisation of the artist acting as a conceptual converter of these inventive representations into a coherent proposal, as his spirit lies behind each image, without him having taken any of them; also, by the fact that they reveal the free-flowing waving of identity in the turbulent waters of the 21st century. In this sense, the series brilliantly suggests that identity has never before been so malleable, prescribing a self that is expanded, flexible, fragmented, expendable. Anticipating the condition of the produser (in which everyone can be both a producer and a user of images), the series poignantly raises the question of whether photography can still capture a coherent idea of the self or contributes to its constant reinvention and reconstruction within virtual small worlds. And while one might think that Martin Parr’s Self-Portraits are limited to a parody of self-representation (at a time when this practice appears almost as an imperative duty), they also seem to allude to the ubiquity of the photographic medium which, in the post-photographic web age, still offers itself as part of a popular, unpredictable social rite. Moreover, they seem to hint at the central role our image plays in the ephemeral colonialism of mass tourism.